|

On the occasion of the strike in November-December 2019, Liam Shields wrote a post To Strike or Disrupt on whether or not people on research leave should go on strike, since their withdrawing of their labour does not cause much disruption to normal proceedings.

Liam argued that on the basis of the principle of maximising disruption, these people should, rather than work to contract and donate their salary to the fighting fund, which enables colleagues in precarious positions to go on strike. On the occasion of the upcoming strike (February-March 2020), it seemed appropriate to me to recall Liam's argument and to flesh out some implications and worries a bit further. You can read my full post on Justice Everywhere.

0 Comments

In this post for Justice Everywhere, I engaging with some of the fascinating ideas discussed by Samuel Scheffler in his 1986 article Morality’s demands and their limits and his 1992 book Human morality. His observations and questions do not seem to leave me at peace and require much further reflection.

Pursuing our personal, valuable projects often conflicts with requirements of morality. One way to solve this dilemma is to limit the scope of morality by excluding certain areas of life or activities from moral assessment and holding that moral demands do not apply to them. I argue, building on Scheffler's diagnosis, that such strategies remain unsuccessful. Morality appears to be pervasive. It pervades all areas of life. So we have to look elsewhere to solve the dilemma - by evaluating acts, their impacts, theor context, alternatives, and the agents involved. Please visit Justice Everywhere to read the full post. Some theorists argue that contemporary problems such as climate change, sweatshop labour, biodiversity loss, … are New Harms – they are unprecedented problems, and differ in important respects from more familiar harms. Intuitively, this view seems to make sense, but in this blog post for Justice Everywhere I argue that this view is mistaken.

I’ll briefly discuss slavery and the depletion of the ozone layer as examples and then go on to discuss some lessons we can draw from these analogies. For example, one of the problems that renders climate change so much harder to tackle than the depletion of the ozone layer is the much deeper entrenchment of greenhouse gases. In contrast to substances that deplete ozone layer (which were used in a limited number of applications), greenhouse gases are the by-product of virtually any human activity, and our economy quite frankly relies on them. However, consider the analogy with slavery: at some point, slavery was entirely accepted throughout the world and seemed essential to the economies of Great Britain and the USA. Despite this entrenchment, the British were highly committed to dismantling their slave trade and to persuading other nations to do the same. This is encouraging, because it shows that it is possible to change harmful activities, even if they are deeply entrenched. Other lessons can be drawn from history. I hope that the brief examples in the blog post show that we can indeed abandon the view that contemporary harms are new. This should be cause for optimism, because it means that we can indeed learn from our successes and failures in dealing with harms of the past. Please visit Justice Everywhere for the original post. This post is based on a paper I wrote with Derek Bell and Joanne Swaffield, and which is now published in Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics As the famous adage holds, we should try to Do More With Less. We’re living in a time in which minimalism has become a movement and to Marie Kondo has become a verb. As we all know, materialism is bad for the planet and people around us, but in this blog post for Justice Everywhere, I only focus on how self-interest might also be a significant motivator to reduce our materialism, and also give a humble suggestion as to what fundamentally underlies moving to Doing More With Less (or getting even better at it if you’re already on the programme).

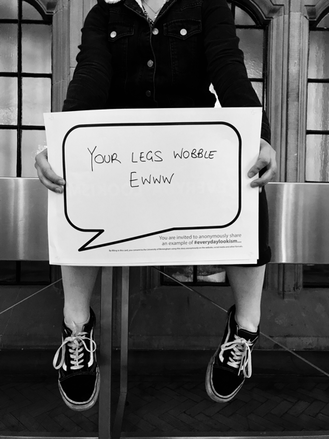

Consumerism is not making us happy, because it tries to fill up the bottomless depths of the Empty Self, we have a relentless desire for more and new stuff, even though this will only satisfy us for a moment. Research has shown time and again that beyond the point of subsistence needs, material wealth has little relationship with wellbeing. Materialistic values are associated with a pervasive undermining of people's personal wellbeing. Consumerism leads to consumer anxiety, work stress, and materialistic pursuits thwart other pursuits and other sources of life satisfaction, the most important of which are mainly non-material in nature: leisure, interpersonal relationships, community involvement, cultural and political participation, recognition, self-respect, and personal growth. In the documentary Minimalism, A documentary about the important things, influential American Professor of Sociology Juliet Schor provocatively says that we are actually not materialistic enough: "We are too materialistic in the everyday sense of the world. And we are not at all materialistic enough in the true sense of the word. We need to be true materialists, like really care about the materiality of goods. Instead we’re in a world in which material goods are so important for their symbolic meaning, what they do to position us in the status system based on what advertising or marketing says they’re about." You can read the entire blog post on Justice Everywhere. In this blog post for Justice Everywhere, I am not developing a new argument. Rather, I pay tribute to the work of my friend and colleague Heather Widdows's fascinating work on Beauty. She is the author of Perfect Me. Beauty as an ethical ideal (Princeton University Press, 2018). In this video, Heather gives a very quick introduction to her main argument in Perfect Me: In my blog post, I try to do two things. First, I summarise my take on Heather's argument very briefly, with a focus on how the beauty ideal is not all evil: it also offers pleasurable individual and communal practices; (many forms of) body work are good for us; beauty objectification can be empowering, protective, promising, and transforming; and beauty can serve some egalitarian purposes in that it shortcuts some existing power hierarchies, and erodes some harmful social features (such as class and wealth) which have traditionally structured society. However, we will have to prevent a bleak future scenario in which the beauty ideal becomes increasingly narrow, demanding, punishing, divisive, and thus increasingly harmful. And rather nurture and facilitate the positive aspects of beauty – those that enhance, respect, connect, and cherish people. One of the main actions to be undertaken to this effect is to end Lookism. In our visual and virtual culture, our bodies have become our selves, and therefore when we shame bodies, we actually shame people. Negative comments about other people’s bodies cut deeply and are unacceptable prejudice. This is lookism, and it has to stop.

Sharing these lookism experiences can also have a more immediate and intrinsic effect as well because it can be helpful in processing such negative experiences. It can be immensely important for people who have been (or are being) subjected to lookism to know that they’re not alone, and that other people (victims and non-victims alike) reject it as the prejudice it is. And it is exactly this that can empower us to end everyday lookism.

What can philosophers do? This campaign will only succeed if we all work together. One of the tasks of philosophers would be to analyse the instances of everyday lookism in order to identify possible structures and trends behind them. In addition, the data consisting of real and highly specific instances gives us a firm ground to methodically examine the prejudices involved, to report these harms in the public domain, and to influence policy. Finally, I believe that our theoretical work on collective action, structural injustice, and responsibility can inform the campaign and the steps to be undertaken to end everyday lookism. The complete Blog Post can be read on Justice Everywhere, here. Voluntary offsetting allows you to ‘neutralise’ your carbon dioxide emissions by preventing the same amount of carbon dioxide from being emitted by someone else, most often somewhere else. Offsetting is a very polarised issue: some defend it as an effective way for individuals to neutralise their carbon emissions, while others have fiercely opposed it as a morally dubious practice

In this post, I take a position in the middle: I believe that under some conditions, emitting-and-offsetting should be morally acceptable. Briefly, these conditions are:

On the basis of these conditions, I can recommend the following organisations to offset your emissions: I explain the reasoning behind the conditions into some more detail in the original Blog Post for Justice Everywhere. However, I feel that this already long post does not yet sufficiently explain my position, so I am thinking about writing a full paper about this. I'll keep you posted! The theme of the 2018 World Environment Day (5 June 2018) was Beat Plastic Pollution. Plastic pollution is indeed a serious problem, severely affecting animals, humans, and ecosystems. Removal of the pollutants that are already in the environment is exceedingly difficult, so in this blog post for Justice Everywhere, I try to address the question as to how we can avoid plastic and other pollutants entering the environment in the first place?

Three variables determine environmental impact: Population, Affluence, and Technology. It is appealing to focus on only one of these variables and expect an easy-fix solution, but we should really address all three factors simultaneously. There is not one panacea, because there are some physical, social, and ethical limits to the extent to which we can reduce the impact of each factor. Moreover, on all three dimensions, we can already take small actions, which combined already significantly reduce humanity's environmental impact. We would also have to take the three factors into account because there are some interactions between them that we should monitor. Finally, there are a lot of ethical issues involved, such as the relation between individual actions and political institutions, gender justice, power relationships between rich and poor, and the traditional (but arbitrary and artificial) separation between private and public sphere. These issues cannot be avoided if we focus on one factor only. An integral approach is likely to do better in this respect. The original post for Justice Everywhere can be read here. The Paris Agreement on Climate Change has been heralded as a monumental succes, but others have also already expressed strong criticism.

I agree that it does seem appropriate to call the Paris Agreement historical: the global context of power and economic inequalities notwithstanding, the countries around the globe have succeeded in reaching a unanimous, legally binding, and substantial agreement about the future of the planet. Nonetheless, the success of the agreement will depend on its translation into practical action and policy, and especially on the following additional factors

The framework set out by the Paris Agreement remains to be translated in effective action and policy measures, and I really hope that it does not remain an empty box... Please read the original blog post on Justice Everywhere. There is always much debate about what our governments and political institutions should do in order to tackle climate change. Important as this may be, I believe this focus should not obscure the role of individuals, but in the general perception as well as some accounts in climate ethics, individuals do not appear to be responsible for climate change, or have any agency in tackling it.

I believe this view is mistaken. In this series of blog posts for Justice-Everywhere, I try to address some pervasive, but (in my view) misleading assumptions regarding individual responsibility for climate change and offer some fresh arguments. I briefly summarise them here - please click on the titles to go to the original posts on Justice Everywhere.

In sum, as Dale Jamieson's puts it so eloquently: "Biking instead of driving or choosing the veggie burger rather than the hamburger may seem like small choices, and it may seem that such small choices by such little people barely matter. But ironically, they may be the only thing that matters. For large changes are caused and constituted by small choices." |