|

As the famous adage holds, we should try to Do More With Less. We’re living in a time in which minimalism has become a movement and to Marie Kondo has become a verb. As we all know, materialism is bad for the planet and people around us, but in this blog post for Justice Everywhere, I only focus on how self-interest might also be a significant motivator to reduce our materialism, and also give a humble suggestion as to what fundamentally underlies moving to Doing More With Less (or getting even better at it if you’re already on the programme).

Consumerism is not making us happy, because it tries to fill up the bottomless depths of the Empty Self, we have a relentless desire for more and new stuff, even though this will only satisfy us for a moment. Research has shown time and again that beyond the point of subsistence needs, material wealth has little relationship with wellbeing. Materialistic values are associated with a pervasive undermining of people's personal wellbeing. Consumerism leads to consumer anxiety, work stress, and materialistic pursuits thwart other pursuits and other sources of life satisfaction, the most important of which are mainly non-material in nature: leisure, interpersonal relationships, community involvement, cultural and political participation, recognition, self-respect, and personal growth. In the documentary Minimalism, A documentary about the important things, influential American Professor of Sociology Juliet Schor provocatively says that we are actually not materialistic enough: "We are too materialistic in the everyday sense of the world. And we are not at all materialistic enough in the true sense of the word. We need to be true materialists, like really care about the materiality of goods. Instead we’re in a world in which material goods are so important for their symbolic meaning, what they do to position us in the status system based on what advertising or marketing says they’re about." You can read the entire blog post on Justice Everywhere.

1 Comment

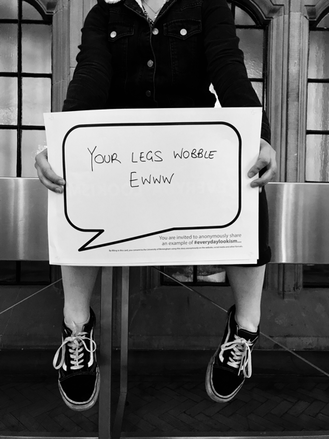

In this blog post for Justice Everywhere, I am not developing a new argument. Rather, I pay tribute to the work of my friend and colleague Heather Widdows's fascinating work on Beauty. She is the author of Perfect Me. Beauty as an ethical ideal (Princeton University Press, 2018). In this video, Heather gives a very quick introduction to her main argument in Perfect Me: In my blog post, I try to do two things. First, I summarise my take on Heather's argument very briefly, with a focus on how the beauty ideal is not all evil: it also offers pleasurable individual and communal practices; (many forms of) body work are good for us; beauty objectification can be empowering, protective, promising, and transforming; and beauty can serve some egalitarian purposes in that it shortcuts some existing power hierarchies, and erodes some harmful social features (such as class and wealth) which have traditionally structured society. However, we will have to prevent a bleak future scenario in which the beauty ideal becomes increasingly narrow, demanding, punishing, divisive, and thus increasingly harmful. And rather nurture and facilitate the positive aspects of beauty – those that enhance, respect, connect, and cherish people. One of the main actions to be undertaken to this effect is to end Lookism. In our visual and virtual culture, our bodies have become our selves, and therefore when we shame bodies, we actually shame people. Negative comments about other people’s bodies cut deeply and are unacceptable prejudice. This is lookism, and it has to stop.

Sharing these lookism experiences can also have a more immediate and intrinsic effect as well because it can be helpful in processing such negative experiences. It can be immensely important for people who have been (or are being) subjected to lookism to know that they’re not alone, and that other people (victims and non-victims alike) reject it as the prejudice it is. And it is exactly this that can empower us to end everyday lookism.

What can philosophers do? This campaign will only succeed if we all work together. One of the tasks of philosophers would be to analyse the instances of everyday lookism in order to identify possible structures and trends behind them. In addition, the data consisting of real and highly specific instances gives us a firm ground to methodically examine the prejudices involved, to report these harms in the public domain, and to influence policy. Finally, I believe that our theoretical work on collective action, structural injustice, and responsibility can inform the campaign and the steps to be undertaken to end everyday lookism. The complete Blog Post can be read on Justice Everywhere, here. |